SSW alumnus working to reform national child welfare system

April 3, 2020

By David Miller

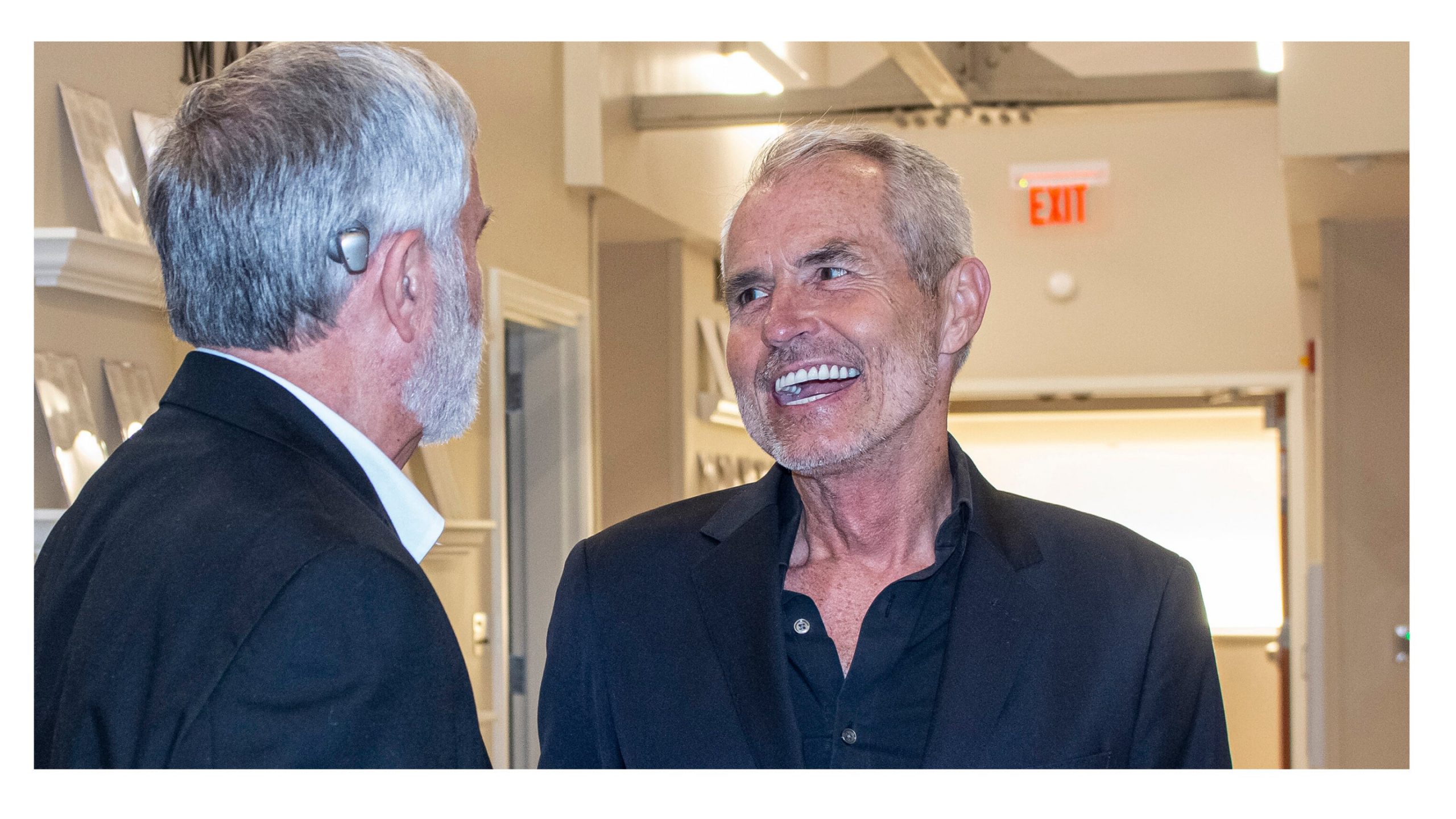

Jerry Milner, currently the associate commissioner at the Children’s Bureau, poses for a photo with Dr. Javonda Williams, associate dean for academic programs and student services.

Jerry Milner’s quest to shift United States child welfare policy to a holistic, data-driven system comes with many challenges.

Milner, associate commissioner at the Children’s Bureau since November 2017, says that the “wheels of government” don’t always match the pace of his plans for the Bureau. And, as an appointed official, his time in the role is indefinite, potentially limiting his ability to “do very big things.”

There’s also the challenge of changing a historical mindset and practice of child welfare being a reactive system, which has implications beyond improving outcomes; a major shift to a proactive, family-centric system changes how many social workers and administrators do their jobs, Milner said.

“I want to move us into a system where we’re strengthening families before something bad happens to them,” Milner said. “That may seem pretty simple, and a lot of people, on the surface, may agree with that. But when you start changing policy, trying to change funding to support that kind of vision, it’s incredibly difficult.

“But that’s the kind of system that will serve us well.”

After 45 years working in child welfare, Milner has developed the patience, tact and resilience needed to match his ambitious vision to reform a decades-old system. These traits and expertise started in Alabama, where Milner earned his MSW and DSW degrees at The University of Alabama School of Social Work, and served as the state’s child welfare director.

Milner said the challenges he faces in Washington, D.C. mirror what he experienced more than two decades ago in Alabama, where he worked to move an engrained system in a very different direction.

“The whole foundation for what I’ve been working on here in D.C. is just an outgrowth of the experience we had in Alabama,” Milner said. “We had a rare opportunity there to use something as adverse as a class action lawsuit to totally rethink the way we did our business with children and families.”

Milner celebrates with his children after earning his DSW at UA.

Under the leadership of Milner and his predecessor, fellow School alumnus Paul Vincent, Alabama redeveloped its child welfare system in the 1990s, with a focus on preserving families and abandoning its “rescue the child” philosophy, which often meant separating children from their families as the primary and initial reaction by social workers and the courts.

“Sometimes the courts felt only way to protect children was to take them away from their parents,” Milner said. “You had service providers whose only livelihoods was providing foster or group care, and trying to move that system to home-based and community-base was very difficult. It’s very hard for people to give up their commitment to a way of doing work that’s very comfortable to them, particularly if their livelihood depends on it.”

Despite the challenges, child welfare leaders and funders in Alabama were able to influence change in policy, practice and training, as well as fund the reformed child welfare system in Alabama. The experience “shaped my whole view of what we need to do” in child welfare, he said.

“The absolute joy in that was seeing it could work, and seeing that we were not compromising child safety by helping children remain in homes with their families,” Milner said. “We had the data to show us children were no less safe when we kept them away from the trauma of separation.”

The advent of analytics as a primary driver of decision-making in both the public and private sector has created sophisticated methods to determine which metrics are relevant and how to interpret data correctly. Milner said social workers have been historically “notorious” for their hesitancy to use data, opting instead to only rely on field experiences to make decisions. But there’s been a shift in that ethos, and it’s helped grow the broader spectrum of social work into a sophisticated, more successful profession, he said.

During Milner’s DSW dissertation, data was one of two hallmarks that would prove “foundational” for the work he’s doing at the federal level. The other was to engage with the people you’re tasked to serve, especially when working in leadership roles. Milner’s dissertation explored the factors that affect the length of time children spend in foster care.

“One of the major factors had to do with engaging parents and parent-child interaction while a child is in foster care, and the effect it had on the length of time a child would spend in the foster system,” Milner said. “Those kinds of factors are essential to the vision that we have right here today in the Children’s Bureau. It’s noteworthy to me – that was 35 years ago – the same kinds of issues are there that we’re promoting and dealing with at the Bureau. In many ways, that’s incredibly affirming to me.”

Milner continues to keep a standard of leading from the field. He’s on the road at least once a week, visiting with families across the country to better understand their needs, experiences and dynamics.

“It’s easy in Washington, D.C. to become a bureaucrat,” he said, “to lose touch with the day-to-day reality of the families that our programs are designed to serve. I’m able to deal with that by being on the road, to meet with those families, to hear from them directly and meet with the young people to understand what worked and didn’t work for them.

“I’d encourage anyone who comes Washington and aspires to work here to stay as connected to the people we’re serving and the programs we’re funding as they possibly can.”

NOTE: This story originally appeared in the 2020 edition of Outreach, the School of Social Work’s annual report.