Hoover native completes MSW-MPH program

By David Miller

April 27, 2021

Niya Bonner could see the disparities of the “black experience” all around her.

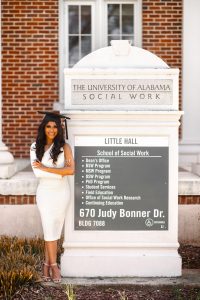

Niya Bonner, Hoover native and Spring 2021 MSW-MPH graduate.

Her relatives in rural areas and inner cities in Alabama experienced the same barriers to affordable medication and healthcare. And, as Bonner grew older and began to understand how diabetes and hypertension affect her family, she began to ask “why?”

To that point, she’d mainly viewed and addressed societal inequities through church service projects. From organizing and donating to clothing drives for tornado relief, to working in kitchens at shelters, Bonner says she’s been “blessed” with a more rounded perspective.

“People have instilled in me that I could have easily had another life,” Bonner says.

While service is a root for making change, Bonner has been motivated to create a broader, more sustainable impact in communities across Alabama. It’s the reason she decided to pursue an MSW-MPH dual-degree at The University of Alabama, and the mission on which she’ll soon embark when she earns her graduate degree Friday.

“I’m interested in maternal and child health, where disparities play a role in outcomes,” Bonner said. “I want to help improve care and access to care for underserved communities and minority populations, and I have a great opportunity to do that in both fields.”

The grind

Completing the MSW-MPH program is incredibly rewarding, given the challenges of balancing classwork, internships and work, Bonner says.

She struggled, initially, to balance everything, often neglecting to “focus on myself until the end” of the program.

“I was working at a hospital full-time, and there were times I’d fallen asleep at my lap-top … fully dressed,” Bonner said. “You have to be organized, manage your time, and practice self-care.”

Part of limiting stress and practicing self-care – particularly during the pandemic – meant knowing when to ask for help, or simply “saying no.” Bonner says she wasn’t afraid to tell her professors when she was overwhelmed.

“I was that student, but my teachers were understanding,” Bonner said. “I also leaned on my classmates – don’t be afraid to ask them questions.”

The payoff

Bonner’s second-year field placement was at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Pediatric Pulmonary Center, which contained many non-traditional elements of training that go beyond patient care.

This placement was Bonner’s first where she was the only social worker, but working in interprofessional and interdisciplinary teams helped her learn the infrastructure of modern healthcare, and how providers operate within that structure. But it also revealed gaps in healthcare that she’d witnessed previously.

“In that internship, you deal with some tough DHR reports and issues with travel,” Bonner said. “I was surprised how many people travel from out of state, some living as far as five hours away, with children who are [at UAB] regularly. So, you look at things like that – this is the only hospital catered to children – and you see other states and wonder why we have just one.”

These observations helped inform a research project at UAB in which Bonner and her fellow trainees completed a year-round project on barriers, accessibility and evaluation of telehealth visits for children with chronic respiratory conditions. The findings will be revealed during her Capstone presentation in May.

Additionally, the team is planning a conference for school nurses in the Birmingham area, which will include mental health topics.

“Niya is well-respected by her fellow trainees and faculty,” says Claire Lenker, Bonner’s field instructor. “She is a true team player and an outstanding social work intern.”

The future

Bonner hopes to open a private practice in an African-American and/or underserved community, where she can be an “open resource” to as many people as possible.

She’s keen to connect with people whose issues aren’t shown on the surface. For instance, she recalls many of her friends who moved around frequently when they were children, though she never understood why.

“I grew up in Hoover, and in bigger, more affluent areas like this, along with Mountain Brook and Vestavia, you don’t see a lot of [African-Americans],” Bonner said. “A lot of people can’t afford to live in these areas, and when I got older, I learned that, in a lot of instances, when [African-Americans] start showing up, it gets more expensive for minorities to stay there.”

Financial stresses and discrimination aside, Bonner hopes to address the self-imposed barriers that keep members of the Black community from getting help, even when dealing with mental health issues or unforeseen tragedies.

“We’re prideful in the Black community because we deal with so much and feel like we can deal with anything,” Bonner said.

Though eager to get started, Bonner’s ambition is measured. She says a private practice will only be as effective as the leadership and guidance she’ll receive throughout her career.

“I’m happy to wait for that chapter,” Bonner said. “My aunt has been a social worker for 20 years and just started her private practice. I think about the needs before anything, and the needs will always be there, so I’ll always have that desire.”