MSW alumna, author reflects on life in policing, social chasm of 2020

July 16, 2020

By David Miller

TK Thorne’s first post-MSW job wasn’t what she envisioned: grant writing for a police department.

But, at the time, she was keenly familiar with the Birmingham Police Department, which had developed a pipeline in the 1970s for University of Alabama MSW graduates to work with police “a lot like the kind of program reformers are talking about doing now,” Thorne said.

While pursuing her MSW at the UA School of Social Work, Thorne wrote a paper about the BPD’s social work program, which led to then-BPD Chief Jim Parsons offering her a job.

“I’d always wanted to be a writer,” Thorne said, “and though it wasn’t what I had in mind, I said ‘yes.’”

In 1976, her first grant project was applying for funds for a computer-aided dispatching system for the police department. She often rode with patrol officers to better understand what they did and what they needed. But in just over a year in that role as a grant writer, Thorne was “bored.”

Additionally, her clinical and field experiences as a social worker – including an undergraduate internship with the Department of Youth Services – were “overwhelming, with multiple issues plaguing each family.” Thorne wanted the ability to intervene on the spot without the prolonged worrying for clients and the uncertainty of her impact as a social worker.

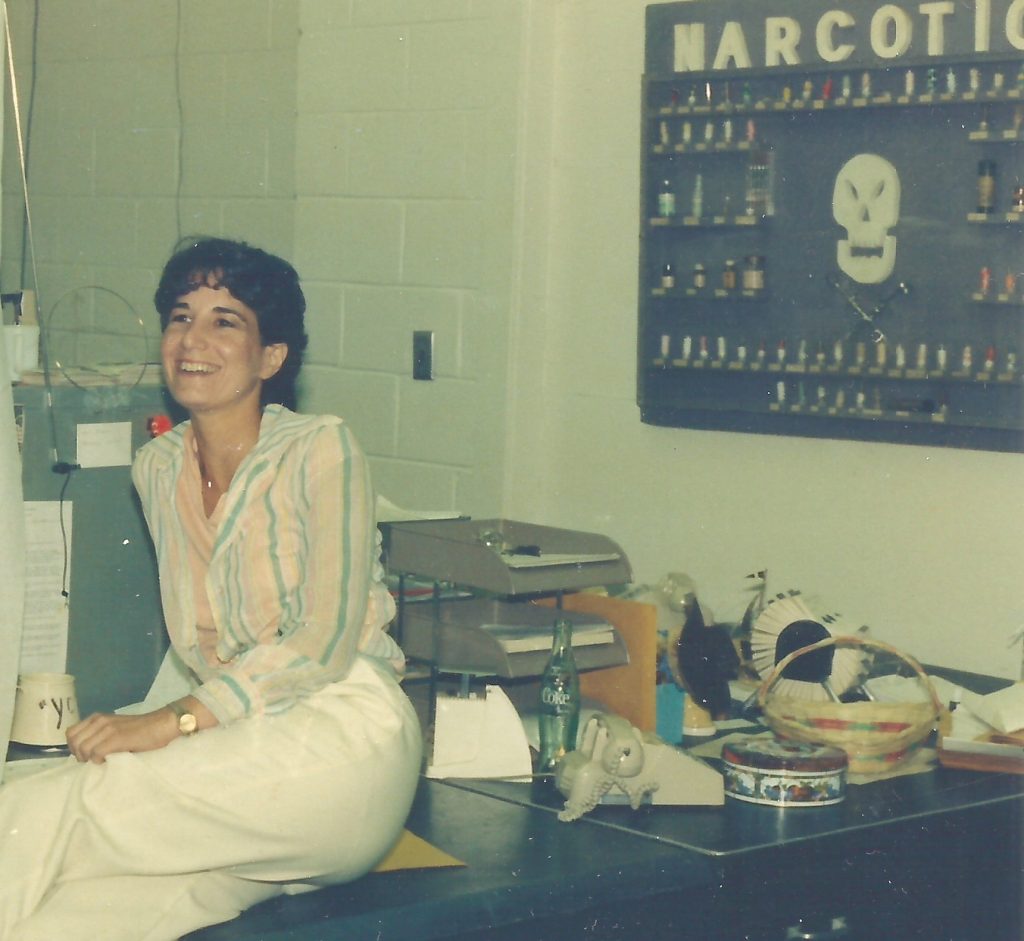

So, she became a police officer with the BPD. She started in patrol before ascending to the position of burglary detective and lieutenant in robbery, and then vice and narcotics, where she would eventually meet her current husband, Roger. She would retire as a precinct captain.

“I didn’t know if I’d stick with it – I had never picked up a gun before the [police] academy,” Thorne said. “But I knew it fit me better. If I saw a child in an abusive situation, I could do something right there. I always felt I was helping, doing crisis-intervention work.”

Thorne says her work as a police officer “broadened” her life experiences and helped develop “my capacity for empathy and compassion,” which influences both her writing – she’s an award-winning novelist – and her perspective on the role social work plays in the future of policing.

Thorne draws literary inspiration from the events of 2020, particularly the social uprising following the “blatant lynching” of George Floyd and other violent interactions involving police and black citizens. In her blog, Thorne addresses officers uncharacteristically “breaking their code of silence” and empathizes with the Black struggle. As a Jewish woman amid growing anti-Semitism around the world, she understands that outpourings of support, while welcome, do not equate with feeling safe.

Still, as cataclysmic as 2020 has been, the stories of this year aren’t surprising to Thorne, who grew up in Alabama during Jim Crow and served as a police officer in the post-civil rights era.

“In the late 1970s, there was a tremendous amount of bottled up anger and frustration in the Black community,” Thorne said. “They’d dealt with a lot of things and simply didn’t trust the police.”

Thorne is no stranger to researching and documenting American civil rights; her non-fiction book, Last Chance for Justice: How Relentless Investigators Uncovered New Evidence Convicting the Birmingham Church Bombers, details the investigation of the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing, a pivotal moment in civil rights history.

Writing, either through her books or her blog, is cathartic for Thorne. But a cultural chasm looms, and real change is needed in policing, prompting greater reflection as “a fish outside the aquarium.” For instance, she questions the “paramilitary” organization, training, and culture of police departments and feels it is the wrong model for modern policing.

“I’m two decades from what’s going on now, but it’s always seemed strange,” Thorne says, “that you train like you are in the military, while the reality is in most places police officers are working alone and in many rural areas, backup can be a long way away. There is no sergeant standing over your shoulder telling you what to do, like in the military. Of course, a situation can change quickly, but for the most part, police are dealing with civilians, not enemy combatants.

“So, the whole mindset is nuts. If you look at the history of policing, it didn’t start out that way. It was more social work in the beginning, more community policing. Then, we went through a period of professionalism, which gave us patrol cars and instant communication, and a lot of it made policing more efficient. But it wormed in a philosophy and identity as a ‘crime fighter, not a social worker.’ So, do you try to make police into social workers, or pair them with social workers? Or both? That’s difficult to answer.”

Thorne’s experiences inform as nuanced of a perspective as one could have, but solutions for police reform are just as intricate, even when distilled to the role of intervention, she says.

“There are so many entangled social problems that have nothing to do with police themselves, but they’re supposed to solve them,” Thorne says. “Problems like drug addiction, homelessness, mental illness, poverty, etc. are underlying factors in the situations police are called upon to solve, but the only tool they have is arrest.

“Social workers have the opposite limitation: they don’t have arrest power. In domestic violence cases, studies have shown that the only thing that has real success is to arrest and prosecute the perpetrator, but if you’re a social worker, you don’t have that option.

Thorne said both police and social workers need significant expansion of services and resources in order to empower them. For instance, she recommends mental health facilities being available during emergencies – like a typical walk-in emergency room – a concept she “fought a long time for in Birmingham.”

Though police reform hinges greatly on changing paradigms, Thorne warns some drastic changes to the broader criminal justice system might be “cutting off the nose to spite the face.” For example, many prison-alternative programs paired with the court system have had success resolving difficult problems like drug addiction and domestic violence.

“The success rate in these programs is far better than sending someone to prison … it’s cheaper even,” she says. “Interestingly, these programs are successful because they’re in the criminal justice system, and judges are able to provide motivation for offenders to take advantage of the resources available to them – resources, ironically, they might not have access to outside the system. That is not to say changes shouldn’t be made. The criminal justice system in the U.S. is broken in many ways, but we do need to keep in mind what kinds of interventions have been successful and make sure if we do away with them, we have affordable and effective alternatives in place, and that we can still protect communities.”

Thorne is currently completing a trilogy of novels set in Birmingham where a police officer discovers she’s a witch. The first story, House of Rose, has been published. She is also working on another civil rights nonfiction book, Behind the Magic Curtain: Secrets, Spies, and Unsung White Allies of Birmingham’s Civil Rights Days, which she expects to be published in 2021.